|

||||||

|

GAY

FILM REVIEWS BY MICHAEL D. KLEMM

|

||||||

|

Rope Warner Brothers, 1948 Director: Screenplay: Starring: James Stewart, John Dall, Farley Granger, Cedric Hardwicke, Constance Collier Unrated, 81 minutes

Compulsion Fox Home Video, 1959 Director: Screenplay: Starring: Unrated, 103 minutes

Swoon Strand Releasing, 1992 Director/Screenplay: Starring: Craig Chester, Daniel Schlachet, Michael Kirby, Michael Stumm, Ron Vawter Unrated, 90 minutes

|

Three

Views To A Kill

Three very different films, each available on video, have been based on the Leopold-Loeb murder case. The first was Alfred Hitchcock's Rope, (1948), a fictionalized look at the killing. The second, Richard Fleischer's Compulsion, (1959), is a fact-based account that focuses on the trial. The third was Tom Kalin's Swoon, (1992). Of the three, only Swoon keeps the original names intact, and depicts the gay relationship between the killers. This review examines their merits as cinema, and not their adherence to facts. |

|

|

|

The best of the three films is Alfred Hitchcock's Rope, which is based on a stage play by Patrick Hamilton, and scripted by gay screenwriter Arthur Laurents. Rope begins with the killing, photographed in tight close-up. Brandon (John Dahl) and Phillip (Farley Granger) have just strangled their college friend David Kentley for the thrill of it. They place his body in a chest in the middle of the living room and then prepare for a dinner party. The food will be served on top of David's "coffin." Among the guests are David's parents. Brandon, to Phillip's horror, has also invited their old college housemaster, Rupert Cadell, (James Stewart) to the party. It was Rupert who first introduced the two boys to the Nietzschean idea of the Superman. Brandon perversely believes that Rupert would approve of their deed, and it is his arrogance that ultimately seals their fates. Hitchcock lets the suspense build as the audience waits for Rupert to put two and two together and discover the murder.

|

|

|

[Reviewer's note 2009: Screenwriter Arthur Laurents and star Farley Granger were lovers at the time of Rope's production. Laurents discusses, in the HBO film of The Celluloid Closet, how they managed to fool the Hays Office and slip all of the gay subtext into the film. Hitchcock took the script and put back in all the English phrases from the original play, such as "my dear boy," that Laurents had removed. The censors circled all of these phrases as being "homosexual dialogue" and missed everything else. Hitch could be quite clever.]

|

|

|

|

|

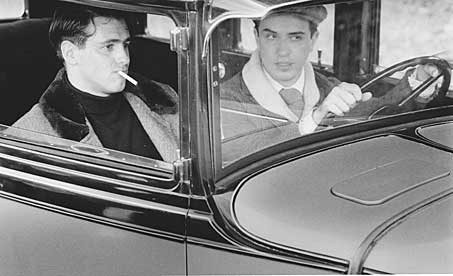

The names are also changed in Compulsion, (based on the book by Meyer Levin), which features Bradford Dillman and Dean Stockwell as Artie Strauss and Judd Stiener, the two young criminals. While Compulsion is the most straightforward re-telling of the case, it is also the weakest and most dated of the three. Director Richard Fleischer seems to be an Otto Preminger-wannabe. The film opens in a sensational vein with loud jazz music accompanying an idiotic credit sequence that depicts the two boys joyriding and running down an old drunk. Filmed in black and white, and in widescreen Cinemascope, the movie suffers from many of the era's cliches.

While Compulsion fully explores the killers' intellects and their embrace of Nietzsche, it completely skirts the issue of their sexuality. Director Fleischer hints at their relationship by often photographing the men in tight close-up, their faces inches away from each other. They never act alone, all crimes are committed together. Artie often "commands" Judd. At one point Artie asks Judd if he is "ditching [him] for some girl." Judd's brother asks him why he doesn't go to baseball games and chase girls. Wilk later says to them: "Aside from each other, you don't have any close friends." He fears what the prosecution may make of this and asks "Any girls?" Given the time devoted to Orson Welles, especially to his closing remarks, Compulsion turns into a social and political soapbox that opposes the death penalty. (This was true of many films at the time.) As an examination of the motives behind the Leopold-Loeb murder, the film is fairly accurate. It is reccommended mostly for Welles' performance as Darrow. In Tom Kalin's controversial Swoon, with Craig Chester as Nathan Leopold and Daniel Schlachet as Richard Loeb, the boys' sexuality is not only addressed but brought to the forefront and made the focus of the movie. Kalin, who wrote, directed and edited the independent film, is less concerned with the boys' motives of Nietzschean intellect and dwells more on their stormy relationship. |

|

|

|

|

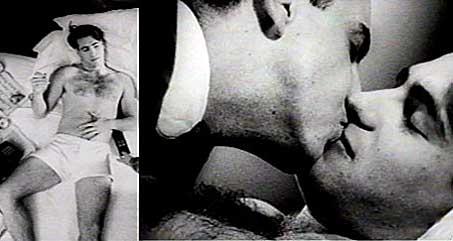

Under the film's credit sequence, Leopold and Loeb walk together through ruined buildings and playfully smash bottles on the ground while a hand-held camera records their childlike destructive revels. Excited, they duck into a corner and kiss. Loeb removes two rings from his mouth in an extreme close-up and places one of them on Leopold's finger. Cut to the two men in bed. A voice-over describes their crimes, intercut with newsreel footage from the 1920s. The scene is charged with sexuality as the camera lingers on their nude bodies. Actual court records report that Leopold was a willing accomplice in exchange for sexual favors, which Loeb gave reluctantly. Their relationship, as presented here, is complex. Loeb, relaxed and smiling in bed, calls out "I suppose you want your payment now" before willingly giving himself to his friend. Later, as they prepare to bury the murdered boy, Loeb stops to kiss Leopold and then pushes him away. Tenderness alternates with anger. During key monents a whip will crack on the soundtrack. Leopold will confess to a psychiatrist that he fantasizes himself as a king on an island who buys "Dickie" as a slave. When arrested, both blames the murder on the other. |

|

|

Filmed in grainy black and white, Swoon is the most self-consciously "artsy" of the three movies. The photography and the editing, while carefully calculated for artistic effect, borders on pretentious at times, and is often confusing on a first viewing. Swoon's visuals are filled with crucial information that can be missed if the viewer is not playing close attention. A virtual catalogue of filmic effects, Swoon is reminiscent of the works of the French New Wave, particularly Truffaut and Godard, with a touch of Fellini for good measure. Kalin also pays a visual homage to Hitchcock at one point, re-creating the famous close-up kiss between James Stewart and Grace Kelly (including the same dialogue) from Rear Window. Swoon is not a film for everyone, but it's well worth a look for its photography and for its portrayal of the killers' sexual dynamics. |

|

|

|

|

In many suspense thrillers, gay characters are often the victims of senseless killings. Over the years, numerous film villians were gay only for their added shock value. Hitchcock's villians in Rope may have been gay, but they were also attractive and fully realized. Arrogant intellect, rather than sexual "perversion," leads to murder. Most of Hitchcock's murderers are usually charming, and Brandon and Philip easily fit this mold, regardless of their sexuality. As for Compulsion, one only needs to look at the film's title to see that its motives were to shock and exploit. Swoon, despite its occasional excesses, is the most honest of the films because it portrays Leopold and Loeb by their own names and defines their passions as both criminal and sexual. Many politically correct gays will probably object to each film's unflattering look at male-to-male love. This reviewer believes that the cinema should present positive and non-stereotypical gay characters for a mass audience, but not to the point where we lose all sense of balance. Should African Americans boycott every film in which the murderer is Black? Despite its past abundance of evil gay killers, it would be ludicrous to purge the cinema of all negative portrayals. The Leopold-Loeb case is a part of history, and hence it is fair game for filmmakers, both gay and straight.

Reviewer/webmaster's note 2007: For anyone who is curious, there is also an acclaimed musical (book, lyrics and music by Stephen Dolginoff) entiitled Thrill Me: The Leopold & Loeb Story. As bizarre as this sounds, the show is quite unique and it actually works. It is a two actor play with a live piano accompaniment and was recently performed here in Buffalo at The New Phoenix Theatre On The Park with Dolginoff in the lead. My interview with him, as well as my poster and production shots can be seen here.

See

also (the review is longer): More On Craig

Chester: More On Alfred

Hitchcock and Farley Granger: |