|

The

Celluloid Closet

HBO Video, 1995

Director/Screenplay:

Rob Epstein,

Jeffrey Friedman

Narration

written by :

Armistead Maupin

from the book by

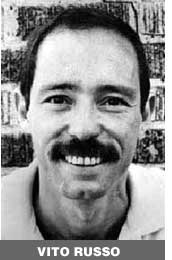

Vito Russo

Starring:

Lily Tomlin, Narrator,

Armistead Maupin, Whoopi Goldberg, Rita

Mae Brown, Quentin Crisp, Harvey Fierstein, Arthur Laurents, Susie Bright,

Gore Vidal, Barry Sandler, Mart Crowley, Jay Presson Allen, Ron Nyswaner,

Paul Rudnick, John Schlesinger, Shirley MacLaine, Farley Granger, Tom

Hanks, Susan Sarandon

Unrated, 102 minutes

|

What

We Learned At The Movies

by

Michael D. Klemm

Reprinted

from Outcome, October,

2001

Extensive

research goes into the making of a documentary, even if much of it never

makes the final cut. It is not uncommon for hours of interview footage

to be discarded. A special edition DVD, therefore, is the ideal format

for viewing a documentary when its audience hungers for more information.

The Celluloid Closet has just

made its debut on DVD and its extras are worth checking out even if you

have already seen, or own, the film on videotape. Extensive

research goes into the making of a documentary, even if much of it never

makes the final cut. It is not uncommon for hours of interview footage

to be discarded. A special edition DVD, therefore, is the ideal format

for viewing a documentary when its audience hungers for more information.

The Celluloid Closet has just

made its debut on DVD and its extras are worth checking out even if you

have already seen, or own, the film on videotape.

Not all of my readers

own a DVD player, so let's start with the film itself before discussing

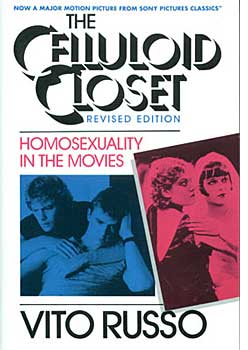

the extras. The Celluloid Closet

(1995) is a very entertaining documentary that chronicles the often tainted

depiction of gays and lesbians on the silver screen. It is based on Vito

Russo's groundbreaking 1981 study, which he updated in 1986. Unfortunately

he did not live to write a third edition to reflect queer cinema's current

accomplishments as he died from AIDS complications in 1990. The filmmakers,

Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, are also responsible for The Times

Of Harvey Milk, Common Threads: Stories From The Quilt, and the recent

Paragraph 172.

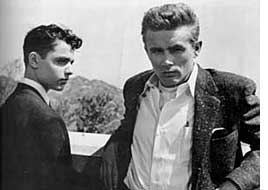

The

film version roughly follows Russo's structure and themes. Utilizing film

clips and interviews, tied together by Lily Tomlin's narration, The

Celluloid Closet takes the viewer through various stages

of Hollywood history from the screaming nellies of 1930s musicals to the

more finely drawn characters of today. It describes how the infamous Hays

Code eliminated all mention of homosexuality from the silver screen and

how several creative directors managed to fool the censors. Relaxing the

code in the 1950s brought out characters like the predatory lesbian. Finally

the 60s begat the self loathing homosexual who kills himself, later followed

by gay pyschopathic killers and ludicrous stereotypes that were always

the butt of insensitive jokes. The

film version roughly follows Russo's structure and themes. Utilizing film

clips and interviews, tied together by Lily Tomlin's narration, The

Celluloid Closet takes the viewer through various stages

of Hollywood history from the screaming nellies of 1930s musicals to the

more finely drawn characters of today. It describes how the infamous Hays

Code eliminated all mention of homosexuality from the silver screen and

how several creative directors managed to fool the censors. Relaxing the

code in the 1950s brought out characters like the predatory lesbian. Finally

the 60s begat the self loathing homosexual who kills himself, later followed

by gay pyschopathic killers and ludicrous stereotypes that were always

the butt of insensitive jokes.

Younger

filmmgoers today have the opportunity to see films like All

Over The Guy at the downtown cinema and do not remember a time when

we were invisible on the screen. There were no positive gay images

on the silver screen when I was growing up. Author Russo, and many

of those interviewed for The Celluloid Closet,

have noted how we were "starving" for positive images of ourselves

in the movies. When homosexuality was depicted, it was something

to laugh at, or to pity. The great Hollywood dream factory taught straights

what to think about gays, and it taught gay people to hate themselves. Younger

filmmgoers today have the opportunity to see films like All

Over The Guy at the downtown cinema and do not remember a time when

we were invisible on the screen. There were no positive gay images

on the silver screen when I was growing up. Author Russo, and many

of those interviewed for The Celluloid Closet,

have noted how we were "starving" for positive images of ourselves

in the movies. When homosexuality was depicted, it was something

to laugh at, or to pity. The great Hollywood dream factory taught straights

what to think about gays, and it taught gay people to hate themselves.

|

|

But

the filmmakers do more than just assemble film clips. Most of the accompanying

commentaries are both biting and insightful. Many voices are heard as

such gay luminaries as Quentin Crisp, Harvey

Fierstein, Rita Mae Brown, Armistand

Maupin and Gore Vidal (as well as a few token straights like Tony

Curtis, Whoopi Goldberg, Shirley MacLaine and Tom

Hanks) add their own perspectives, both historical and anecdotal.

Barry Sandler, the writer of 1982's Making

Love describes how negatively audiences reacted to Michael Ontkean

and Harry Hamlin's kiss. Screenwriter Arthur

Laurents discusses how Hitchcock made

a film about two obviously gay murderers, 1948's Rope,

without identifying the killers' sexuality. Among my favorite moments

are writer Susie Bright talking about first seeing Marlene Dietrich, dashing

in a tuxedo, kiss another woman in 1930's Morocco one night on

a late show when she was a teenager, and writing an alternate scenario.

She was also stunned when Mrs. Danvers, the evil housekeeper in Hitchcock's

1940 Rebecca lovingly showed the new Mrs. DeWinter her predecessor's

lingerie. Susan Sarandon makes the definite

statement on being straight and playing gay. Commenting on how the director

of 1983's The Hunger wanted her character

to be drunk for the seduction scene, Sarandon replied "I don't have to

get drunk to sleep with Catherine Deneuve!" But

the filmmakers do more than just assemble film clips. Most of the accompanying

commentaries are both biting and insightful. Many voices are heard as

such gay luminaries as Quentin Crisp, Harvey

Fierstein, Rita Mae Brown, Armistand

Maupin and Gore Vidal (as well as a few token straights like Tony

Curtis, Whoopi Goldberg, Shirley MacLaine and Tom

Hanks) add their own perspectives, both historical and anecdotal.

Barry Sandler, the writer of 1982's Making

Love describes how negatively audiences reacted to Michael Ontkean

and Harry Hamlin's kiss. Screenwriter Arthur

Laurents discusses how Hitchcock made

a film about two obviously gay murderers, 1948's Rope,

without identifying the killers' sexuality. Among my favorite moments

are writer Susie Bright talking about first seeing Marlene Dietrich, dashing

in a tuxedo, kiss another woman in 1930's Morocco one night on

a late show when she was a teenager, and writing an alternate scenario.

She was also stunned when Mrs. Danvers, the evil housekeeper in Hitchcock's

1940 Rebecca lovingly showed the new Mrs. DeWinter her predecessor's

lingerie. Susan Sarandon makes the definite

statement on being straight and playing gay. Commenting on how the director

of 1983's The Hunger wanted her character

to be drunk for the seduction scene, Sarandon replied "I don't have to

get drunk to sleep with Catherine Deneuve!"

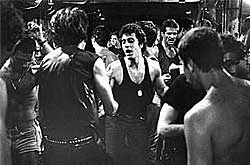

The

humor vanishes while films such as 1980's Cruising

take center stage. Most disturbing was seeing James Caan repeatedly

shoot a transvestite killer in 1974's Freebie and the Bean while

the commentator notes that audiences didn't just cheer the death of the

villian... they cheered the death of the fag. The groundbreaking

Making Love is compared with the same year's

Personal Best as filmgoers prefer to see two women in bed and not

two men. A montage of scenes from independent gay films such as 1986's

Parting Glances and 1990's Longtime

Companion rounds out the documentary on an upbeat note, while brief

snippets from 1991's The Silence of the Lambs and 1992's Basic

Instinct make it clear that Hollywood still likes to add "sexual deviancy"

to the resumes of killers in big budget films. The

humor vanishes while films such as 1980's Cruising

take center stage. Most disturbing was seeing James Caan repeatedly

shoot a transvestite killer in 1974's Freebie and the Bean while

the commentator notes that audiences didn't just cheer the death of the

villian... they cheered the death of the fag. The groundbreaking

Making Love is compared with the same year's

Personal Best as filmgoers prefer to see two women in bed and not

two men. A montage of scenes from independent gay films such as 1986's

Parting Glances and 1990's Longtime

Companion rounds out the documentary on an upbeat note, while brief

snippets from 1991's The Silence of the Lambs and 1992's Basic

Instinct make it clear that Hollywood still likes to add "sexual deviancy"

to the resumes of killers in big budget films.

The

Celluloid Closet's

101 minute running time moves briskly and smoothly, and is a wonderful

and perceptive introduction to this subject. But, for those who are serious

students of the genre, it is too brief and many important films are missing.

European cinema is ignored, and many important figures omitted. And that's

where the DVD comes into play. The new DVD is a must for anyone who is

interested in queer cinema history. First, and foremost, there is an hour

of un-used interviews that didn't make the final cut. Among them are commentaries

from filmmakers Kenneth Anger discussing

his films, 1947's Fireworks and 1963's Scorpio

Rising, and out British film critic Robin Wood commenting on the gay

villians in several Alfred Hitchcock films.

Also included is Gus Van Sant's

revelation that River Phoenix conceived the campfire scene from My

Own Private Idaho. The

Celluloid Closet's

101 minute running time moves briskly and smoothly, and is a wonderful

and perceptive introduction to this subject. But, for those who are serious

students of the genre, it is too brief and many important films are missing.

European cinema is ignored, and many important figures omitted. And that's

where the DVD comes into play. The new DVD is a must for anyone who is

interested in queer cinema history. First, and foremost, there is an hour

of un-used interviews that didn't make the final cut. Among them are commentaries

from filmmakers Kenneth Anger discussing

his films, 1947's Fireworks and 1963's Scorpio

Rising, and out British film critic Robin Wood commenting on the gay

villians in several Alfred Hitchcock films.

Also included is Gus Van Sant's

revelation that River Phoenix conceived the campfire scene from My

Own Private Idaho.

There

is also a full length commentary from the directors and Lily Tomlin. The

commentary is very illuminating and makes clear why certain films, like

1969's Midnight Cowboy for example, were removed for time and pacing

concerns. But it is also notable for the way in which they all talk freely

and openly about their lives. Lily Tomlin has been criticized for years

for having never publicly come out but it is obvious from listening to

her on the disc that she is hiding nothing about her personal life with

Jane Wagner. There

is also a full length commentary from the directors and Lily Tomlin. The

commentary is very illuminating and makes clear why certain films, like

1969's Midnight Cowboy for example, were removed for time and pacing

concerns. But it is also notable for the way in which they all talk freely

and openly about their lives. Lily Tomlin has been criticized for years

for having never publicly come out but it is obvious from listening to

her on the disc that she is hiding nothing about her personal life with

Jane Wagner.

|

|

Also

worth noting is that the commentators' friendships with Vito Russo extended

back to the 1970s and the portrait of the late author is both humorous

and touching. The disc, in fact, has changed my entire perception of Mr.

Russo. I have owned the second edition of his superb book ever since 1987

and have always assumed, from his writing, that he was a very angry man.

Yes, he was also one of the founders of ACT-UP and he had no patience

for gay films that copped out, but the man that emerges on this disc (through

a short filmed interview and a fascinating full-length lecture that occupies

a second separate audio track) is an articulate and very funny

man who laid the groundwork for all serious studies of queer cinema that

would follow. Russo's spoken commentaries, additionally, blow away the

narration that Armistead Maupin wrote

for the film. This is an amazing disc and highly reccommended. Also

worth noting is that the commentators' friendships with Vito Russo extended

back to the 1970s and the portrait of the late author is both humorous

and touching. The disc, in fact, has changed my entire perception of Mr.

Russo. I have owned the second edition of his superb book ever since 1987

and have always assumed, from his writing, that he was a very angry man.

Yes, he was also one of the founders of ACT-UP and he had no patience

for gay films that copped out, but the man that emerges on this disc (through

a short filmed interview and a fascinating full-length lecture that occupies

a second separate audio track) is an articulate and very funny

man who laid the groundwork for all serious studies of queer cinema that

would follow. Russo's spoken commentaries, additionally, blow away the

narration that Armistead Maupin wrote

for the film. This is an amazing disc and highly reccommended.

Reviewer's Note 2007:

I've become aware of a lot of Vito Russo bashing, especially online, from

more and more gay critics. I am presuming that these are mostly younger

writers who, I think, need a reminder again that queer films were not

as visible then as they are now.

Vito Russo died from

AIDS complications in 1990 so there will never be a third or fourth edition

of his 1981 The Celluloid Closet,

revised and updated in 1986. He did not live to see how new queer cinema

exploded a couple years later, after his death. Okay, the book is

sometimes dated. But then, by the same token, so are Pauline Kael's collections

of film criticism from the 60s and so is the classic French film magazine

from the 50s, Cahiers Du Cinema - whose writers included Francois

Truffaut and Jean Luc Godard.

The

Celluloid Closet was the first of its kind. When I first

purchased it in 1987, there were no other books devoted to this

subject. The amount of research (not to mention the number of films he

had to watch) that went into The Celluloid

Closet is staggering and it laid the groundwork for all

queer film criticism to come. Okay, he does protest too much regarding

some films but you have to look at them in their proper context. For example,

Cruising came out when there were no

positive depictions of gays and lesbians onscreen. Russo was part of the

protests during the filming. Were they over-reacting as many contemporary

writers accuse? No, they weren't - even if it seems that way now. Gay

bashings went up after Cruising played. My partner counseled gays

at the college where he taught, and he got panicky calls from many young

men asking if that is going to be what their lives will be.

It would have been

different if Will and Grace had been on TV for years before a film

like Cruising hit the screens, but it wasn't like that in the 70s.

We had Three's Company instead. Only fags existed onscreen.

Hence the anger throughout The Celluloid Closet.

If those of us from the "Old Guard" were always asking if a

film was good for gays it was because the majority of the movies out there

weren't good for gays. We were hairdressers, we were psycho killers.

It was a different time. And the book reflects that time.

Though Russo does

make a few mistakes, it is a valuable reference book. He can also be faulted

for shortchanging a lot of European cinema - Fassbinder's

films, for example, are never even mentioned in the text. Despite

these faults, it is still, to my mind, the definitive book on the subject...

at least up to 1986. It's up to new writers to write about the rest. I've

tried, myself, to write about as many as I can in Outcome

and they're all here on this site. Russo's book is a good gateway to our

cinematic history and it helps, in order to ground new writings, to know

our past and what came before. Then you are aware of what traditions a

new work upholds and what new ground it may be breaking. If you don't

like Russo's politics, if it's too 1980s-ACT UP for you, then just read

about the movies and learn where we have come from. After you read about

films like The Detective, Scarecrow, Reflections In A Golden Eye

and The Fox, you might start to understand his "whining."

More on Rob Epstein

and Jeffrey Friedman:

Howl

See also

Vito

Fabulous: The Story of

Queer Cinema

This Film Is Not Yet

Rated

Lavender

Limelight

Click here for

more on Vito Russo

gmax.co.za

|