|

||||||

|

GAY

FILM REVIEWS BY MICHAEL D. KLEMM

|

||||||

|

The Naked Civil Servant BBC Video, Director: Screenplay: Starring: Unrated, 87 minutes

An Englishman in New York Breaking

Glass Pictures / QC Cinema, Director: Screenplay: Starring: Unrated, 75 minutes

Red Ribbons Waterbearer Films, Director/Screenplay: Starring: Unrated, 64 minutes |

To

The Beat Of A Different Drummer

Savoring every moment of a truly outstanding acting performance is one of life's great pleasures. I'm talking about when an actor completely becomes the character he or she is playing and you can't take your eyes from the performer. I'm talking Gary Oldman as Joe Orton in Prick Up Your Ears; Derek Jacobi in I, Claudius; Ian McKellen in Richard III; John Lithgow's recent stint as a serial killer on Dexter. John Hurt's outrageous, yet perceptive and sensitive, portrayal of Quentin Crisp in The Naked Civil Servant (1975) falls under this umbrella. As a gift to audiences everywhere, Hurt has just reprised the role of Crisp - as an old man - in 2009's An Englishman in New York. |

The

Naked Civil Servant is

based on the 1968 autobiography by Quentin Crisp. An

Englishman in New York, titled after the song by Sting (written

for Crisp), draws from many sources to depict Crisp's twilight celebrity

life in America. The new film doesn't shy away from depicting a major controversy

and this will be discussed later. This review examines both of these films

in their proper sequence. An Englishman in New

York is the new release but the narrative arc will be better

if we begin with The Naked Civil Servant. The

Naked Civil Servant is

based on the 1968 autobiography by Quentin Crisp. An

Englishman in New York, titled after the song by Sting (written

for Crisp), draws from many sources to depict Crisp's twilight celebrity

life in America. The new film doesn't shy away from depicting a major controversy

and this will be discussed later. This review examines both of these films

in their proper sequence. An Englishman in New

York is the new release but the narrative arc will be better

if we begin with The Naked Civil Servant.

|

|

|

|

|

The

Naked Civil Servant,

made for British television in 1975, is a remarkable mix of high camp and

pathos. Its achievement is extraordinary, especially when one considers

how astonishingly un-apologetic it is for a movie filmed during the 1970s.

Need I mention how queers were being depicted on America's screens, big

and small? The film's approach is often as iconoclastic as its subject and

rich with humor. Swinging big band standards from the period keeps the mood

lively. The narrations are both fabulous and dark with irony. These are

augmented, usually for comic effect, by silent film title cards. Framed

by an ornate Art Nouveau border are such epithets as "Sexual intercourse

is a poor substitute for masturbation" and "Exhibitionism is a drug. You

get hooked." The

Naked Civil Servant,

made for British television in 1975, is a remarkable mix of high camp and

pathos. Its achievement is extraordinary, especially when one considers

how astonishingly un-apologetic it is for a movie filmed during the 1970s.

Need I mention how queers were being depicted on America's screens, big

and small? The film's approach is often as iconoclastic as its subject and

rich with humor. Swinging big band standards from the period keeps the mood

lively. The narrations are both fabulous and dark with irony. These are

augmented, usually for comic effect, by silent film title cards. Framed

by an ornate Art Nouveau border are such epithets as "Sexual intercourse

is a poor substitute for masturbation" and "Exhibitionism is a drug. You

get hooked." |

|

Director

Jack Gold wisely opens his film with an introduction by the real Quentin

Crisp in all his queenly glory. This was a good thing because otherwise

the average viewer might assume that John Hurt must be exaggerating

his performance. The first time we see him he is posing in front of a full

length mirror. His stuffy father enters and snips, "Do you intend to spend

your entire life admiring yourself?" His son replies, "If I possibly can." Director

Jack Gold wisely opens his film with an introduction by the real Quentin

Crisp in all his queenly glory. This was a good thing because otherwise

the average viewer might assume that John Hurt must be exaggerating

his performance. The first time we see him he is posing in front of a full

length mirror. His stuffy father enters and snips, "Do you intend to spend

your entire life admiring yourself?" His son replies, "If I possibly can."

|

|

Philip

Mackie's script captures the man's acerbic wit and Hurt brings Crisp vividly

to life. He is exotic. He is so alien and so weird that audiences

won't feel threatened; you can't help but embrace him. Holding his head

high, he sashays through the streets, ignoring the stares and the insults.

He knows what he is doing and it is his middle finger extended out at the

world. His attitude invites admiration. When Crisp is stopped by the police

and called a pansy, he replies, "I don't know any other meaning of this

word apart from being a flower." The other world, he tells a friend, is

something he doesn't wish to join. When war is declared in 1939, he buys

two pounds of Henna. There is a truly ugly moment when he is beat up by

a group of thugs (recalling a similar scene in A Clockwork Orange)

but, retaining his dignity, he rises bloodied to ask "Have I annoyed you

gentlemen in some way?" Philip

Mackie's script captures the man's acerbic wit and Hurt brings Crisp vividly

to life. He is exotic. He is so alien and so weird that audiences

won't feel threatened; you can't help but embrace him. Holding his head

high, he sashays through the streets, ignoring the stares and the insults.

He knows what he is doing and it is his middle finger extended out at the

world. His attitude invites admiration. When Crisp is stopped by the police

and called a pansy, he replies, "I don't know any other meaning of this

word apart from being a flower." The other world, he tells a friend, is

something he doesn't wish to join. When war is declared in 1939, he buys

two pounds of Henna. There is a truly ugly moment when he is beat up by

a group of thugs (recalling a similar scene in A Clockwork Orange)

but, retaining his dignity, he rises bloodied to ask "Have I annoyed you

gentlemen in some way?" |

|

Poor

Quentin doesn't fit in anywhere. He even experiences homophobia from his

own kind when he is asked to leave a gay establishment because he would

give all of them away to the police by being so obvious. But that

was Mr. Crisp's specialty. He didn't care what anyone thought. There is

a marvelous scene in which he appears in court on trumped up indecency charges.

When asked if he would like to make his statement from the docks or take

the witness box, his voice-over announces that he "can't possibly play [his]

big scene with [his] back to the audience." He speaks with such dignity

in his defense that he is able to make a political statement while still

winning the courtroom's hearts. Poor

Quentin doesn't fit in anywhere. He even experiences homophobia from his

own kind when he is asked to leave a gay establishment because he would

give all of them away to the police by being so obvious. But that

was Mr. Crisp's specialty. He didn't care what anyone thought. There is

a marvelous scene in which he appears in court on trumped up indecency charges.

When asked if he would like to make his statement from the docks or take

the witness box, his voice-over announces that he "can't possibly play [his]

big scene with [his] back to the audience." He speaks with such dignity

in his defense that he is able to make a political statement while still

winning the courtroom's hearts. |

|

Vito

Russo wrote in The Celluloid

Closet that Crisp was not a gay liberationist's dream but conceded

that you had to admire the man's courage. The

Naked Civil Servant was well received critically and Hurt

won a BAFTA award for his starring role. There was controversy too, (did

you expect otherwise?), especially when PBS aired it in America. The film

brought the real Mr. Crisp his fifteen minutes of fame and this part of

his life would be dramatized thirty-three years later in the new film, An

Englishman in New York. Vito

Russo wrote in The Celluloid

Closet that Crisp was not a gay liberationist's dream but conceded

that you had to admire the man's courage. The

Naked Civil Servant was well received critically and Hurt

won a BAFTA award for his starring role. There was controversy too, (did

you expect otherwise?), especially when PBS aired it in America. The film

brought the real Mr. Crisp his fifteen minutes of fame and this part of

his life would be dramatized thirty-three years later in the new film, An

Englishman in New York. |

|

You

will be seriously charmed by Hurt's delightfully fey portrayal in both films.

There is one unforgettable scene after another. A man pulls him into an

alley for a quickie ("The great thing about following an obvious homosexual

is that you can't possibly be wrong"). Witness his joy when he meets more

of his kind for the first time in the Black Cat Cafe. One of his new friends

gives Crisp a tube of lipstick which he rapturously accepts. He works as

a nude model for an art class (hence the film's title). He enjoys a lot

of sex with soldiers during the war. For a brief time he dabbles in the

world's oldest profession. At a tea party, he so shocks his mother's friend

that she gasps, "Oh dear, your son isn't one of those, is he?" You

will be seriously charmed by Hurt's delightfully fey portrayal in both films.

There is one unforgettable scene after another. A man pulls him into an

alley for a quickie ("The great thing about following an obvious homosexual

is that you can't possibly be wrong"). Witness his joy when he meets more

of his kind for the first time in the Black Cat Cafe. One of his new friends

gives Crisp a tube of lipstick which he rapturously accepts. He works as

a nude model for an art class (hence the film's title). He enjoys a lot

of sex with soldiers during the war. For a brief time he dabbles in the

world's oldest profession. At a tea party, he so shocks his mother's friend

that she gasps, "Oh dear, your son isn't one of those, is he?" |

|

Hurt

is one of our most distinguished living character actors. He literally disappears

into his performance as Crisp. In lesser hands, Crisp could have been a

cartoon. You laugh with him and not at him. Hurt doesn't

hold back on the foppery but he also finds the humanity beneath. Despite

his appearance, he stands his ground with dignity and there is great strength

behind the makeup. His face, even as a young man, is a roadmap of emotions.

He skillfully makes the outlandish plausible. He's a Kabuki dandy interpreted

with grace and subtlety. Quentin Crisp was the role that Hurt was born to

play. Hurt

is one of our most distinguished living character actors. He literally disappears

into his performance as Crisp. In lesser hands, Crisp could have been a

cartoon. You laugh with him and not at him. Hurt doesn't

hold back on the foppery but he also finds the humanity beneath. Despite

his appearance, he stands his ground with dignity and there is great strength

behind the makeup. His face, even as a young man, is a roadmap of emotions.

He skillfully makes the outlandish plausible. He's a Kabuki dandy interpreted

with grace and subtlety. Quentin Crisp was the role that Hurt was born to

play. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| It would be hard to imagine this movie without Hurt. The same is true for its sequel, An Englishman In New York. The new movie, directed by Richard Laxton from a screenplay by Brian Fillis, begins almost where the first one left off, with Crisp suddenly finding himself in demand on talk shows following the release of The Naked Civil Servant film. Crisp's wit, if anything has gotten better with age. "All my newfound celebrity meant was that my tormentors could put a name to their demon." Crisp tells us when he receives a phone call from a man threatening to assault him. "Would you like to make an appointment? Crisp, deadpan, replies to be his would-be assailant, "I have some time on Tuesday afternoon if that's convenient." | |

Crisp

is invited to America to perform in a one man show and, in 1981, establishes

permanent residence in New York City. During these shows he regales the

audience with stories of his life and then delights them further by taking

questions. The show is a hit. He acquires an agent, played by Swoosie Kurtz.

"You're different," she tells Crisp. "People like different." She lands

him a gig writing movie reviews for The New York Native. Crisp and

the magazine's editor, Phillip Steele (Denis O'Hare), become close friends.

The Steele character combines Crisp's real-life personal assistant, Phillip

Ward, and Native/Christopher Street founding editor, Tom Steele.

They go to see Tootise together and Crisp commends Mr.Hoffman for

his "courage." Crisp

is invited to America to perform in a one man show and, in 1981, establishes

permanent residence in New York City. During these shows he regales the

audience with stories of his life and then delights them further by taking

questions. The show is a hit. He acquires an agent, played by Swoosie Kurtz.

"You're different," she tells Crisp. "People like different." She lands

him a gig writing movie reviews for The New York Native. Crisp and

the magazine's editor, Phillip Steele (Denis O'Hare), become close friends.

The Steele character combines Crisp's real-life personal assistant, Phillip

Ward, and Native/Christopher Street founding editor, Tom Steele.

They go to see Tootise together and Crisp commends Mr.Hoffman for

his "courage." |

|

Crisp

loves New York and he adores stardom. Crisp tells friends that he has stopped

buying food and simply attends every cocktail party to which he is invited.

Expected to "sing for his supper" at these functions, he downplays being

a "hero" and remains largely apolitical. When he sashays down the streets

now, he revels in the way that everyone is on display and not just

him. The mood is, again, exuberant and the music during these early scenes

is a hybrid of "Theme from Shaft" and 70s television fodder like

Charlie's Angels and Starsky and Hutch. The right comic touches

are nailed and viewers will, again, be enchanted. Crisp

loves New York and he adores stardom. Crisp tells friends that he has stopped

buying food and simply attends every cocktail party to which he is invited.

Expected to "sing for his supper" at these functions, he downplays being

a "hero" and remains largely apolitical. When he sashays down the streets

now, he revels in the way that everyone is on display and not just

him. The mood is, again, exuberant and the music during these early scenes

is a hybrid of "Theme from Shaft" and 70s television fodder like

Charlie's Angels and Starsky and Hutch. The right comic touches

are nailed and viewers will, again, be enchanted. |

|

Those

familiar with The Naked Civil Servant

will recognize Crisp's aversion to housework when the camera pans through

his messy apartment. ("After four years, the dust doesn't get any worse.")

We are also reacquainted with Crisp's futile quest to find the "great dark

man" of his dreams who would never be interested in him. During

a visit to The Anvil, (in flagrant disregard of the legendary bar's dress

code), Crisp observes the leather men and clones and notes that "they operate

on the principle that in order to find the great dark man you first have

to look like him." In a scene that mirrors one from the first film, Crisp's

appearance is at such odds with the rest of the bar's butch clientele that

he is asked to leave. Those

familiar with The Naked Civil Servant

will recognize Crisp's aversion to housework when the camera pans through

his messy apartment. ("After four years, the dust doesn't get any worse.")

We are also reacquainted with Crisp's futile quest to find the "great dark

man" of his dreams who would never be interested in him. During

a visit to The Anvil, (in flagrant disregard of the legendary bar's dress

code), Crisp observes the leather men and clones and notes that "they operate

on the principle that in order to find the great dark man you first have

to look like him." In a scene that mirrors one from the first film, Crisp's

appearance is at such odds with the rest of the bar's butch clientele that

he is asked to leave. |

|

Thus

far, the film has been fun. But then viewers who aren't intimate with Crisp's

background will receive an unexpected jolt. An

Englishman In New York doesn't shy away from the more controversial

facets to Crisp's twilight years and Fillis' script is a warts-and-all portrait

of the artist. Crisp became anathema to the gay community in 1983 with his

own John Lennon "The Beatles are bigger

than Jesus" faux pas. During one of his shows, Crisp is asked about AIDS

and he shocks his audience by replying that "homosexuals are forever complaining

about one ailment or another. AIDS is a fad, nothing more." Suddenly there

is no more laughter, just dead silence. Thus

far, the film has been fun. But then viewers who aren't intimate with Crisp's

background will receive an unexpected jolt. An

Englishman In New York doesn't shy away from the more controversial

facets to Crisp's twilight years and Fillis' script is a warts-and-all portrait

of the artist. Crisp became anathema to the gay community in 1983 with his

own John Lennon "The Beatles are bigger

than Jesus" faux pas. During one of his shows, Crisp is asked about AIDS

and he shocks his audience by replying that "homosexuals are forever complaining

about one ailment or another. AIDS is a fad, nothing more." Suddenly there

is no more laughter, just dead silence. |

|

Coupled

with his previous dismissal of gay liberation, and his refusal to get involved

in gay causes, the backlash is immediate. Crisp's speaking engagements are

canceled, he loses his writing gig with the Native. Ignoring the

advice of his colleagues, he refuses to retract or apologize for his ill

chosen words. To do so, he claims, would call into question everything he

has ever said. It is hard to comprehend that Crisp could have been so oblivious

but how could he know, at the time, that AIDS would still have no

cure almost thirty years later? His thoughtless observation is still inexcusable,

yet he is strangely prophetic when he says that "to create a hysteria around

this disease would play into the hands of your enemies. They would say that

homosexuality and disease go hand in hand." (Jesse Helms and Pat Buchannon

anyone?) Coupled

with his previous dismissal of gay liberation, and his refusal to get involved

in gay causes, the backlash is immediate. Crisp's speaking engagements are

canceled, he loses his writing gig with the Native. Ignoring the

advice of his colleagues, he refuses to retract or apologize for his ill

chosen words. To do so, he claims, would call into question everything he

has ever said. It is hard to comprehend that Crisp could have been so oblivious

but how could he know, at the time, that AIDS would still have no

cure almost thirty years later? His thoughtless observation is still inexcusable,

yet he is strangely prophetic when he says that "to create a hysteria around

this disease would play into the hands of your enemies. They would say that

homosexuality and disease go hand in hand." (Jesse Helms and Pat Buchannon

anyone?) |

|

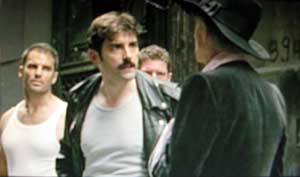

Crisp

is directly confronted by a group of leathermen about his comments during

the film's best scene. The set-up closely resembles one of the street scenarios

in which was Crisp was beaten up in the first movie. Crisp is taken aback

by their accusations and the look on his face as he finally comprehends

the full weight of his insensitive remarks is devastating. At a loss for

words, he comes the closest that he ever will to delivering an apology.

("I must insure that the words that upset you are never said again.") Words

aren't even necessary to convey his inner turmoil; Hurt's craggy face almost

erodes in front of us and the light extinguishes from his eyes. Crisp

is directly confronted by a group of leathermen about his comments during

the film's best scene. The set-up closely resembles one of the street scenarios

in which was Crisp was beaten up in the first movie. Crisp is taken aback

by their accusations and the look on his face as he finally comprehends

the full weight of his insensitive remarks is devastating. At a loss for

words, he comes the closest that he ever will to delivering an apology.

("I must insure that the words that upset you are never said again.") Words

aren't even necessary to convey his inner turmoil; Hurt's craggy face almost

erodes in front of us and the light extinguishes from his eyes. |

|

Two

story arcs dominate the rest of the film's running time. Crisp befriends

a young gay artist named Patrick Angus (Jonathan Tucker) and helps him achieve

modest success before he succumbs to AIDS complications. Angus, like Crisp,

also doesn't believe in love and refers to the subjects of his paintings

as his great dark men. "There is no great dark man," Crisp sadly tells him.

"I know, I've looked." After a ten year hiatus from the stage, Crisp joins

forces with performance artist Penny Arcade (Cynthia Nixon) for a series

of shows. As he grows ancient before our eyes, Steele becomes Crisp's caregiver

and the touching relationship that grows between them almost resembles that

of a longtime married couple. There is a lot of talk about death during

the last scenes; some of it witty, some of it schmaltzy. Crisp has mellowed

and there's a wonderful moment where Steele discovers that the old writer

has been sending checks to AIDS charities. Characteristically, Crisp insists

"It's just so I can meet Miss Taylor." Two

story arcs dominate the rest of the film's running time. Crisp befriends

a young gay artist named Patrick Angus (Jonathan Tucker) and helps him achieve

modest success before he succumbs to AIDS complications. Angus, like Crisp,

also doesn't believe in love and refers to the subjects of his paintings

as his great dark men. "There is no great dark man," Crisp sadly tells him.

"I know, I've looked." After a ten year hiatus from the stage, Crisp joins

forces with performance artist Penny Arcade (Cynthia Nixon) for a series

of shows. As he grows ancient before our eyes, Steele becomes Crisp's caregiver

and the touching relationship that grows between them almost resembles that

of a longtime married couple. There is a lot of talk about death during

the last scenes; some of it witty, some of it schmaltzy. Crisp has mellowed

and there's a wonderful moment where Steele discovers that the old writer

has been sending checks to AIDS charities. Characteristically, Crisp insists

"It's just so I can meet Miss Taylor." |

|

Hurt,

again, is outstanding as Crisp. He is equally adept at capturing the man's

catty wit, his arrogance, and finally his intense sadness as he grows older

and older. His flamboyance diminishes with age and it is almost painful

to watch his slow deterioration. The make-up job on Hurt as he ages is superb.

The film's second half loses steam in spots but always remains engaging

because of Hurt. The Naked Civil Servant

is the better of the two movies, but An Englishman

In New York is a worthy successor. I find few flaws but the

new film seems more like a made-for-televison movie than its predessesor,

expecially when the director insists on adding banal piano cues to accompany

Crisp's meaningful stares when silence would have been more effective. But

my quibbles are small because, even at its weakest moments, Hurt continues

to command your attention and Crisp's story is one well worth telling. Hurt,

again, is outstanding as Crisp. He is equally adept at capturing the man's

catty wit, his arrogance, and finally his intense sadness as he grows older

and older. His flamboyance diminishes with age and it is almost painful

to watch his slow deterioration. The make-up job on Hurt as he ages is superb.

The film's second half loses steam in spots but always remains engaging

because of Hurt. The Naked Civil Servant

is the better of the two movies, but An Englishman

In New York is a worthy successor. I find few flaws but the

new film seems more like a made-for-televison movie than its predessesor,

expecially when the director insists on adding banal piano cues to accompany

Crisp's meaningful stares when silence would have been more effective. But

my quibbles are small because, even at its weakest moments, Hurt continues

to command your attention and Crisp's story is one well worth telling. |

|

|

Both discs feature superb supplements. The Naked Civil Servant sports an informative commentary by Hurt and the director, and An Englishman in New York contains a documentary plus a featurette on Hurt as Crisp. Both discs are highly recommended.

|

|

|

|

| The real Quentin Crisp has a major supporting role in Red Ribbons, a 1994 film from writer/director Neil Ira Needleman. Red Ribbons is a comedic drama that tells the story of a group of friends who meet to pay tribute to a fallen comrade, Frank David Niles, who has just died from AIDS complications. Niles (Christopher Cappiello) was the founder of In Your Face, a controversial theatre troupe. The man's plays included such titles as The Trojan War: A Condom Caper, Pink Triangles and Two Lesbians From Verona. It is the day after his funeral and his surviving partner, Robert (Robert Parker), finds himself with an apartment full of visitors who have come to pay their respects. | |

The

guests include his sister, Carolyn (Princess Sandlin), a gay theatre critic

from The Village Voice (William J. Ingersol), and several members

of Niles' theatrical troupe: a lesbian couple (Lee Sharmat, Colleen O'Neill)

and two hammy actors, who are also longtime partners, played by Quentin

Crisp and Victor Burgess. (Crisp's character is named Horace Nightingale

III.) Carolyn's homophobic ex-husband stops by to sign divorce papers, and

Robert is dreading a visit from Niles' estranged mother, played by former

porn actress Georgina Spelvin (The Devil In Miss Jones). The film,

shot with a handheld video camera, combines the events at this gathering,

supplemented by flashbacks via Niles' video diary. The

guests include his sister, Carolyn (Princess Sandlin), a gay theatre critic

from The Village Voice (William J. Ingersol), and several members

of Niles' theatrical troupe: a lesbian couple (Lee Sharmat, Colleen O'Neill)

and two hammy actors, who are also longtime partners, played by Quentin

Crisp and Victor Burgess. (Crisp's character is named Horace Nightingale

III.) Carolyn's homophobic ex-husband stops by to sign divorce papers, and

Robert is dreading a visit from Niles' estranged mother, played by former

porn actress Georgina Spelvin (The Devil In Miss Jones). The film,

shot with a handheld video camera, combines the events at this gathering,

supplemented by flashbacks via Niles' video diary. |

|

Combing

pathos and over-the-top comedy, Red Ribbons

is a well-meaning but ultimately amateurish film. Calling it "stiff"

would be polite. The acting ranges from good to terrible. From the amount

of scene chewing that goes on, I suspect that most of the cast consists

of stage actors who needed to be told to tone it down for the camera. Crisp

looks like a wax figure throughout. Entire scenes are usually played out

in one shot and this was probably a budgetary choice rather than an aesthetic

one. The subject is worthy of our consideration, its execution just leaves

much to be desired. Much of Red Ribbons

is painful. It's hard not to laugh at lines like "Another martyr... how

many martyrs must there be.... the streets are sacrificing you, you and

every other queer with AIDS!" Yet every time I was going to eject the disc,

something would happen to seize my interest. The trouble is, these moments

usually don't last for very long. Combing

pathos and over-the-top comedy, Red Ribbons

is a well-meaning but ultimately amateurish film. Calling it "stiff"

would be polite. The acting ranges from good to terrible. From the amount

of scene chewing that goes on, I suspect that most of the cast consists

of stage actors who needed to be told to tone it down for the camera. Crisp

looks like a wax figure throughout. Entire scenes are usually played out

in one shot and this was probably a budgetary choice rather than an aesthetic

one. The subject is worthy of our consideration, its execution just leaves

much to be desired. Much of Red Ribbons

is painful. It's hard not to laugh at lines like "Another martyr... how

many martyrs must there be.... the streets are sacrificing you, you and

every other queer with AIDS!" Yet every time I was going to eject the disc,

something would happen to seize my interest. The trouble is, these moments

usually don't last for very long. |

|

|

Nevertheless, the movie is a time capsule of sorts. I received no press on this film, and pickings on the web are slim, and so I know nothing about anyone except Crisp and the former porn queen (and that only through imdb.com listings). But it might be safe to assume that the actors were known in the New York City theatre and art circles. Admirers of Mr. Crisp might be captivated by his final feature film appearance, even if he seems to be sleeping through parts of it. The DVD also includes three short films by the same director, Aunt Fannie (also starring Crisp), Renovation, and The Divine Ms. Q, an excerpt from one of Crisp's one man shows.

John Hurt also

appears in: Denis O'Hare also

appears in: Quentin Crisp

also appears in: |

|

|

|